This is an English language translation, the interview originally appeared in Polish in Tygodnik Polityka in August 2017.

What are memory laws?

While the concept of memory laws is constantly evolving, one may generally define it as laws that attempt to shape the collective perception of the past. Some take the form of criminal laws, others of mere solemn declarations, such as parliamentary resolutions commemorating a particular historical event. Proponents of their adoption claim that their intended purpose is to preserve the memory of historical truth. Their opponents describe them as an unacceptable attempt by those in power to impose a single right view of the past. However, both groups should remember the words of Hannah Arendt, who rightfully claimed that fragile memories of facts are susceptible not only to oblivion, but also to manipulation.

Historical propaganda?

Unfortunately, these very memory laws frequently become dangerous tools. Every state has the right to pursue its own “historical policy”. But if such policy is to be defined in law, it is vital to ensure that no specific historical narrative is appropriated.

In our MELA project, we not only analyze and compare national memory laws but also seek to guide on how to avoid their abuse. We look into how memory laws affect societies that are confronted with a specific vision of history of their state and nation, enshrined in law.

Have memory laws been enacted all around the world? In every culture?

Yes, they have. This in fact manifests just how universally communities and nations around the world share the need to shape the way they remember themselves. And how universally those in power are tempted to influence that memory.

Every country struggles with its past demons: the persecution of the Aborigines in Australia, the history of slavery and racial segregation in the United States, the denationalization of the Sami minority in Norway.

Memory laws have a long history. The ones I chose to investigate are nevertheless created in response to the atrocities of World War II, including those of the Holocaust. One set of such laws is the prohibition of genocide denial.

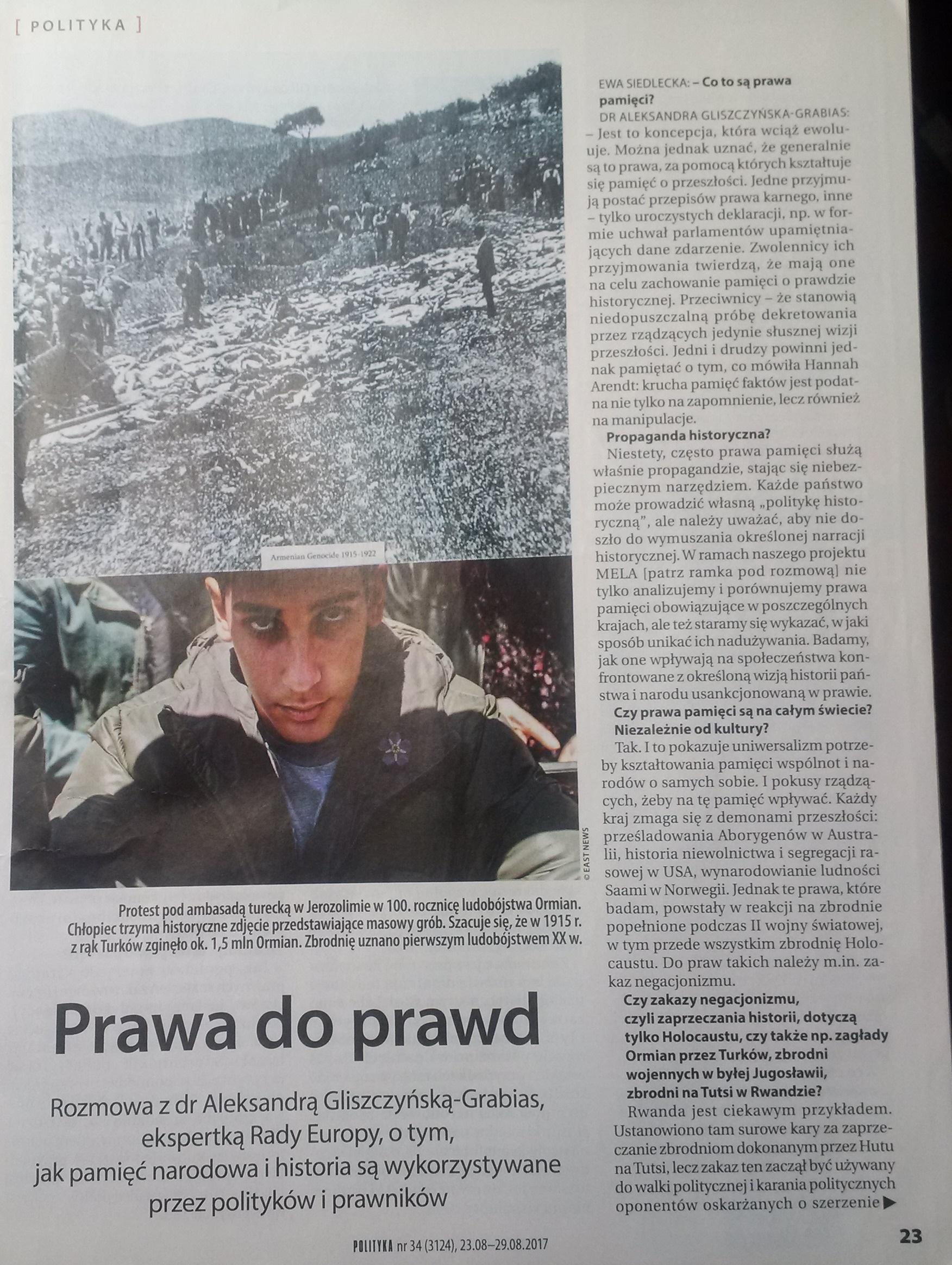

Do denial bans only apply to the Holocaust or are they also concerned with the Armenian genocide committed by the Turks, the war crimes in the former Yugoslavia, and crimes against the Tutsis in Rwanda?

Rwanda is an interesting case. Although the country severely punishes the denial of the crimes committed by the Hutus against the Tutsis, the ban was high-jacked for political purposes and is now used to punish political opponents accused of propagating negationism.

Many countries have a major problem with the enforcement of Holocaust denial ban. Heated debates, some of them among lawyers, have sprung up over the matter. I personally lean towards the belief that Holocaust denial is unique in the sense of all such lies being motivated by anti-Semitism. The penalization of Holocaust denial is thus a way to combat anti-Semitism as a form of racial and ethnic hatred.

However, the Tutsi, Roma and Armenian genocides have also been driven by ethnic hatred. Just like the denial of these crimes.

This precisely is what is being debated: the extent to which the denial of the extermination of Jews, driven by prejudice and hatred, differs from the denial of other events, such as the Armenian genocide, which are driven by the same motives. This very dilemma was faced by the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg in 2015 in the case of Perinçek v Switzerland. Switzerland made genocide denial a criminal offense. The Turkish lawyer and politician Perinçek who went there to deliver a negationist lecture, ended up with a criminal sentence. The Court stated that the Swiss courts convicted Perinçek exclusively for “propagating his views”. It noted further that since the Swiss lack strong historical ties to the Armenian genocide, the memory of this event does not warrant particular protection. Especially that the crimes are already a century in the past.

However, when the Strasburg Court received appeals regarding convictions for the Holocaust denial – of which there were at least a dozen – it never considered whether a given state had any particular connection with the extermination of Jews or how much time since the tragic events had elapsed. The Court always categorically stated that Holocaust denial is a form of anti-Semitism and, as such, is not protected by freedom of expression. Tin my opinion, in the Swiss case, he Court failed to provide compelling arguments to justify its belief that the denial of crimes against the Jews can be banned in all countries while crimes against the Armenians cannot. Thus, the controversy surrounding the Perinçek judgment lies in its adoption of a sort of hierarchy of genocides.

And what about the laws prohibiting the discussion of crimes? Such as the Turkish ban on “denigrating Turkishness” by raising the topic of the extermination of the Armenians, or the Polish draft law forbidding “the defamation of the Polish nation”? A legislative proposal has been submitted to the lower chamber of the Polish Parliament (the Sejm) suggesting to broaden the scope of liability for such acts.

This is another aspect of remembrance: law used to ingrain in people certain convictions about the heroism and high moral ground of one’s own nation and erase any disgraceful episodes from collective memory. The stated rationale behind the enactment of the Polish law was to prevent the use of the phrase “Polish death camps”. I agree that the Polish state should respond to such cases. However, rather than attempting to prosecute the foreign authors of such phrases, the government should opt for the more effective option of educating people, diplomatic efforts and public pressure.

The topic that interests me particularly in my memory law research is the specific “matrix” of such laws created to preserve national pride. For example, such a matrix can be observed in areas where Polish, Ukrainian and Russian laws overlap. It is striking to see how these laws contradict each other and how the past confrontation between states and nations has been built into them.

The motion picture Volhynia could well be banned in Ukraine. The Ukrainian law of 2015 protects the dignity and memory of the heroes of Ukrainian independence fighting, including those of the Ukrainian Insurgent Army. Heroes protected by law in one country are seen as criminals in another.

Russia, in its turn, has developed a cult of the “Great Patriotic War”, which is the term it uses for the Second World War. The Russians celebrate - and sanction by law – the country’s World War II martyrdom and the victory of the Russian nation over Nazism. In contrast, under Ukrainian legislation, the Soviets and the Nazis share responsibility for the outbreak of World War II and the crimes committed during its course.

Remarkably, the more pronounced nationalist tendencies become in a given state, the stronger the state’s effort to blot out inconvenient historical facts, and the tougher the sanctions it adopts under its own memory laws. The likely consequences of passing such laws is an escalation of social conflicts, e.g. with respect to national minorities, exacerbated relations between nations and xenophobic sentiments. On the other hand, this may build national identity and pride and strengthen community spirit.

It nevertheless seems that the main effect of such laws is to manipulate social awareness for political purposes. In communist Poland, the Red Army was portrayed as the “liberator”, while no one spoke of “Operation Vistula” or shmaltsovniks (individuals blackmailing Jews who were hiding, or blackmailing the Poles who protected them). Poles did not join Hitler in the attack on Zaolzie. Home Army partisans were branded as “bandits.” The Third Republic of Poland reversed the story – as a consequence, under the rule of the Polish Law & Justice party, a mention of Poles’ involvement in the Jedwabne crimes, the pacification of Belarusian villages in Białystok by Home Army partisans, the shmaltsovniks or the Kielce Pogrom became punishable as “slanderous imputation of crimes to the Polish nation”.

A great deal depends on how such laws are interpreted and applied for reasons other than the desire to erase inconvenient memories. There are also memory laws designed to “beat one’s breast” as an expression of regret. Such laws exist in Germany, applying to the memory of Nazism, as well as in France, which, in 2001, adopted the so-called “Taubira Act” named after the French Guiana-born Member of Parliament Christiane Taubira, enacted in recognition of slavery and slave trade as a crime against humanity, to which France had contributed. The United States, in its turn, has passed a number of declarations on slavery. In 2008, in a speech before parliament, Australian Prime Minister Kevin Rudd apologized to Aboriginal children removed from their biological parents. In Canada, truth and reconciliation commissions have been set up to deal with the crimes committed against indigenous people.

Is vetting also a memory law?

Yes, it is, being one of the legal measures used to settle the score with former regimes. Vetting and decommunization laws are common in post-Soviet states and have repeatedly been dealt with by the Court. It seeks a balance between granting states the freedom to enact legislation designed to find closure with historical dictatorships and protecting the rights and freedoms of individuals. This is because of the very real danger that such memory rights may be used to advance political agendas.

In Poland, vetting was to help ensure “the turnover of elites”. However, it was targeted not as much at the former communist elites as it was at those members of the communist-period underground opposition who rose to power post 1989. The hope was they would turn out to have been secret collaborators with the regime. More recently, “decommunization” laws were used to purge police forces.

Settling the score with a historic regime is one aspect of memory laws. It refers to the “transitional justice” mechanisms, or the justice of the transition periods that follow the toppling of dictatorships. Once that happens, the architects of such legislation must answer the question of whether the law is to exclude from society individuals previously associated with the ruling party? Should such individuals be banned from holding public offices? Should they be stigmatized? Punished? Stripped of their property? How far down the hierarchy should the sanctions apply? States vary widely in the strategies they adopt. These range from decommunization and vetting to setting up “reconciliation commissions”, as was the case in South Africa and Rwanda, where accounts were settled by having the perpetrators meet their victims face to face and by pursuing the policies of expiation, redress and forgiving. This, however, is a specific approach that is culturally specific and probably impracticable in Europe.

What interests me in particular is the way in which the Strasbourg Court deals with settling with the Nazi and Communist past. My research shows that the Court is considerably less inclined to accept attempts by post-communist states to settle with a former regime than those to reconcile with a Nazi and Fascist past.

Why is that?

One of the reasons may be that Nazism and the Holocaust are part of a shared historical identity of the West, and that, after all, the European system of human rights has been created by the countries of Western Europe. It is easier for Western European nations to understand Nazism than it is to comprehend Communism, which they have never experienced. This difference is reflected in various judgments concerning limitations on freedom of expression.

In the past, the Court considered it admissible to pass even very severe punishments for the propagation of Nazi views in Germany and Austria. In contrast, however, both the displaying of communist symbols and the praising of communism were regarded as protected under the freedom of speech. The Court is of the opinion that the danger of Nazi revival remains invariably high.

I am in fact dubious about the ability of Strasbourg judges to assess the risk and differentiate between the feelings of regime victims. In the case of Vajnai v. Hungary brought by a person penalized for publically displaying a symbol of a Red Star on a jacket, the Court stated that although it sympathized with the feelings and suffering of Hungarian citizens in connection with the communist period, it sees no reason to ban the displaying of such communist symbols. The same Court automatically brands Nazi symbols as irreconcilable with the spirit of the European Convention on Human Rights, without any attempt to examine the sensibilities of the regime’s victims or the risk of it being reinstated.

Memory laws tend to refer to “the right to truth”. What is that about? To me, the phrase brings to mind the arguments used by the advocates of extending the scope of vetting as far as possible. Under the widely-known amendment to the vetting law of 2006 made by the Law & Justice and the Civic Platform parties (which was partially contested by the Constitutional Court), employers were given the right to vet their employees.

Memory laws originated in connection with international humanitarian law and South America’s effort to deal with military dictatorships. The main point was to clarify the fates of the thousands of missing people abducted by the regime whose bodies were never found as well as the truth about the origins of the children who during that time were removed from their families and handed over for adoption to members of the regime’s elites. This gave rise to the concept of “the right to truth”, which has since been recognized and applied in a number of judgments by international courts.

Over time, attempts have been made to extend the understanding of “the right to truth” to include, e.g. the right to access documents. Against this background, Poland, for instance, spoke of the right to access Russian documents on the Katyń massacre. On the other hand, in reference to vetting, one proposed the establishment of the right to learn about specific individuals. The problem with this lies in defining the backgrounds that would qualify persons for such investigations, the facts that would be subject to such disclosures and the people who should be given access to such information.

In my view, the right of victims and their families to know the truth about the persecutors and the circumstances of crimes cannot be contested. However, I would be very cautious about establishing the right to “the truth of nations”, because this creates opportunities for abuse and historical propaganda. The disclosure of such “truth” should be left exclusively to historians.