Seventy years ago, on 14 May 1948, David Ben-Gurion, eight hours before the British Mandate over Palestine was set to expire, declared the independence of the State of Israel. Celebrations for this occurrence, in 2018, began at sunset on 18 April and ended on the evening of the following day – due to the date difference between the Gregorian and Jewish calendars.

Following President Trump’s decision, the US administration has moved its embassy from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem on 14 May of this year – a move that has already caused outrage among Palestinians all over the world. The US move is as historically blind as it is politically foolish. It utterly ignores what the dates I have just mentioned represent for the counterpart of a conflict – to say it cynically – that has lasted as long as the State of Israel exists: the Palestinians.

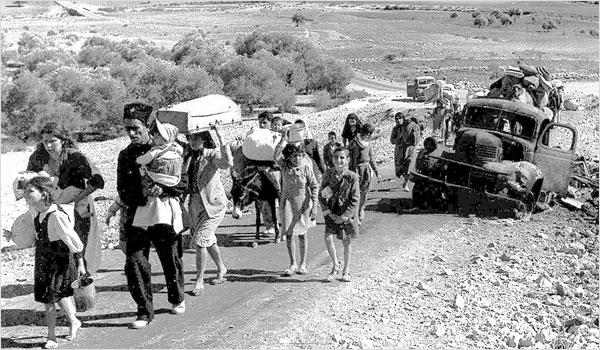

Palestinians consider 15 May one of the most painful days in their calendars. It is the day of the commemoration of the Nakba (in Arabic يوم النكبة or Yōm al-Nakba, the «Day of the Catastrophe»), the ‘uprooting of the Palestinians and the dismemberment and de-Arabisation of historic Palestine’, as Professor Nur Masalha has poignantly defined it in his book The Palestine Nakba. While it is commemorated every year as if it belonged to the past, the Nakba lives on not only symbolically, but also as a unifying descriptor of a constellation of measures enacted by the State of Israel – often in violation of international law – to drastically reduce public spaces for Palestinians.

Celebrations of the Israel Independence Day have obliterated the memory of events such as the Deir Yassin massacre. On 9 April 1948, troops belonging to Zionist paramilitary organisations Irgun and Lehi took over the Arab village of Deir Yassin, near Jerusalem, and slaughtered between 101 and 254 Palestinian villagers in the course of a campaign to lift the Arab blockade of Jerusalem. The massacre shocked Arab communities all over Palestine and pushed entire families to leave their lands before something similar befell them too, as Susan Abulhawa narrates in her heart-rending book Mornings in Jenin.

Similarly, the ‘Great Book Robbery’, the large-scale pillage of books belonging to wealthy Palestinian families of Jerusalem, Jaffa, Nazareth and other cities by either individual or state-sponsored looters, sometimes with the aid of the Israeli army, has largely remained unknown. Some of the stolen books have been reported to have been recycled into paper, whereas others are held in the archives of the National Library of Israel under the authority of the Custodian for Absentee Property. Some still bear the marks of their original owners, including dedications from those who gave them away as presents.

These two episodes are exemplary of an arguably all-encompassing and long-term policy to incrementally shrink public spaces for Palestinian culture, memory and dissent. What many refers to as ‘creeping annexation’ – that is, ‘a putative acquisition of territory … undertaken not in one fell swoop, but gradually through a pattern of oblique and sometimes informal measures’ – to describe the territorial aspect of the prolonged Israeli occupation of the West Bank, East Jerusalem and – arguably – the Gaza Strip could be extended to encompass also the history of the land.

Such – to a certain extent, less tangible – annexation is carried out through a mixture of legislative and administrative actions and the pursuance of a politics of the fait accompli. In the following paragraphs, I seek to cursorily show how seemingly isolated legislative measures appear to contribute to the progressive erosion of Palestinian identity, culture, history and memory.

Section 1 of the Absentee’s Property Law 5710-1950 defines an ‘absentee’ as inter alia a Palestinian citizen who ‘was a legal owner of any property situated in the area of Israel or enjoyed or held it’ and who ‘left his ordinary place of residence in Palestine’. Thus, section 4(a) of the Law empowered the Custodian of Absentees’ Property, appointed by the Minister of Finance under Section 2 of the Law, to take possession of the land belonging to Palestinians who were compelled to flee their land to seek refuge in Jordanian-held territories of historic Palestine or abroad.

This, along with the Land Acquisition Law (Actions and Compensation) of 1953, has resulted in the acquisition by the Jewish National Fund of most of the Palestinian-owned land in Israel (Palestinians living in Israel currently own 3-3.5% of the land, as compared to 48% in 1948). As the ‘Great Book Robbery’ demonstrates, expropriation has concerned not only immovable but also movable property, including books, which are nowadays held by the National Library of Israel.

This move has contributed to the physical and symbolical appropriation by the State of Israel of a cultural and geographical space previously occupied by a lively Palestinian society, which some laudable initiatives, such as the recently opened Palestinian Heritage Museum in the Jerusalem Arab neighbourhood of the American Colony, are seeking to reclaim.

Furthermore, the Law of Return 5710-1950 grants every Jew ‘the right to come to this country as an oleh’ (a Jewish immigrant into Israel), without even mentioning non-Jews – including Palestinians who were forced to abandon their lands for fear of being killed. The Basic Law: Jerusalem, Capital of Israel, passed by the Knesset in 1980, declares that ‘Jerusalem, complete and united, is the capital of Israel’, single-handedly wiping out any Palestinian claim to the Holy City – and in utter disregard of international law.

The State Education Law 5713-1953, as amended in 2000, emphasises the role of State education in perpetuating Jewish and Zionist values while only acknowledging the language, culture, history, heritage and traditions of the Arab population. In a similar fashion, the Broadcasting Authority Law 5725-1965 privileges the diffusion of Jewish culture and traditions among the institutional objectives of the Authority and links them to the purposes of the State Education Law. The Budget Foundations Law (Amendment No. 40) 5771-2011 empowers the Minister of Finance to cut state funding to entities who commemorate ‘Independence Day or the day of the establishment of the state as a day of mourning’, thus violating the Palestinians’ right to commemorate the Nakba.

The Law Preventing Harm to the State of Israel by Means of Boycott 2011 defines the ‘boycott against the State of Israel’ as a civil wrong, including if motivated by the affiliation of the person or body boycotted with an area under the control of the State of Israel – thus, including the boycott against settlement produce. Notwithstanding the illegality under international law of the settlements. In a controversial move that evidences Israeli authorities’ intolerance towards dissent, Human Rights Watch Israel and Palestine director, Omar Shakir, was revoked his work permit over alleged boycott activities on 7 May 2018.

In more recent times, the Israeli authorities have sought to implement a wide range of measures aimed at progressively shrinking public spaces for Palestinians, including discussions on a bill which seeks to limit the Muslim call to prayer between 11pm and 7am, a bill that would allow for closure of organisations critical of the IDF, including for example Breaking the Silence, the enactment of the Entry into Israel Law (Amendment No. 30) 5778-2018, which empowers the Minister of Interior to revoke the permanent residency status to individuals who have performed a ‘deed which involves breach of allegiance to the State of Israel’.

The common thread that connects all these seemingly isolated examples seems to be the progressive and incremental restraint of Palestinian identity, culture, memory and history, which is enacted in – at least – three different ways. First, through what could be seen as cultural appropriation, which includes the use of existing legislation to appropriate material and immaterial artefacts of Palestinian descent. Second, through the dispersion of Palestinian claims to the land, which includes the mythologization of an inextricable and exclusive connection between the land of Palestine (aka Israel) and Jewishness. With a spillover effect into the realm of education and entertainment. Third, through the repression of dissent disguised as safeguard of national security.

Within this trajectory, the Nakba seems only the beginning of a ‘creeping annexation’ of public spaces once occupied by Palestinians. Alternatively, it could be said that the Nakba has never ended and the progression of laws increasingly curtailing the expression of Palestinian claims to their history and land is nothing more than a subtle perpetuation of the Catastrophe.

The Israeli-Palestinian conflict is fought on several grounds – the physical battlefield, bi-lateral negotiations, international institutions and the domestic and international legal arena – but it is also a battle of conflicting narratives, where a party retains superior “firepower” and is able to impose – at least domestically – its own narrative. However, until the original sin – the Nakba – and its repercussions on the subsequent, and still current, Israeli legislative policy are acknowledged and remedied, there cannot be viable prospects of pacification, let alone reconciliation.

This blogpost was first published on openDemocracy’s North Africa West Asia (5 June 2018).

The conclusions in this blogpost illustrate the opinion of its author and do not necessarily illustrate the views of the MELA project.

Piergiuseppe Parisi is doctoral candidate in international criminal justice and international law at the School of International Studies of the University of Trento and research assistant in the HERA-funded project for Memory Laws in European and Comparative Perspective (MELA) in the School of Law at the University of Bologna.