As long as ‘our history’ is legally confined to represent a select group, to the exclusion of others, it isn’t ‘ours’ at all – and neither is it history.

Introduction

The removal of public monuments dedicated to Confederate figures has become a high-volume issue in the United States in recent years. The Charleston Massacre of 2015 served as a catalyst for movements to take down monuments from the Civil War nationwide. Suddenly, the internet was awash with images of protestors pulling statues down with ropes and cars and heated debate concerning Confederate legacies. That discourse has only increased in volume in the years since 2015; in fact, Confederate monument removal was invoked as a political metaphor in major media headlines as recently as November 2018.

For those of us outside the United States in particular, it is hard to know what it is we are looking at. Are the stories we see online the rule or the exception? To what extent does this remain a problem, and what are the implications of these monuments for the communities involved? Moreover, the matter of removing public memorials representing Confederate heroes remains highly political, especially in states formerly part of the Confederacy. The less-discussed aspect is the complex legal structure underlying this issue.

Six states have passed laws preventing the removal of monuments, three of them since the Charleston Massacre in 2015. These laws present obstacles to individuals wishing to petition for a monument’s removal, and often enforce punishments on public institutions that remove monuments themselves. In doing so, they employ reverent language to preserve their telling of the history of the United States Civil War. The end result is the codification into law of a version of the past to which many groups are vehemently opposed. In short, this issue is emblematic of the broad controversial subject of memory laws.

In this post, I will first consider the role history plays in perpetuating past conflicts. I will next summarize the history of Confederate monuments in the United States. Then, I will examine the six memory laws in place preventing their removal. After, I will assess the current state of Confederate monuments in the United States, with particular focus on the six states with anti-monument removal laws in place. Finally, I will conclude on key takeaways from my analysis of this issue.

Terminology

First, a note on ‘history’. The American Historical Association, the largest history education advocacy group in the US, defines the term as comprising “both facts and interpretations of those facts… a monument is not history itself; a monument commemorates an aspect of history”. In other words, history is not understood by modern historians as a discrete set of events to be codified and retold; it is a continuous process, furthered in the act of its interpretation. As Roy succinctly said, there really is “never any end to an event”.

This is not news to political scientists. Robins, though unreasonably dismissive of collective memory, aptly paraphrased Wood and Halbwachs in defining collective memory as “’the selective reconstruction and appropriation of aspects of the past’ that serve as the ‘social frameworks’ onto which personal recollections are woven”. There is also consistent evidence that the continuing interpretation of history has political implications. Indeed, as Graham and Whelan put it, “landscapes of memory are important identity resources for political ideologies in that they can be used to legitimize and/or challenge social and political control.”

Moving from state-interpreted histories to personal ones, Winter considered commemoration of the past as an “act of citizenship”, implying a civic duty to remember history, and therefore necessarily a civic duty to (responsibly) record, interpret, and commemorate the past. Monuments to the past have always been a method used for this purpose, to inscribe “meaning on space”. This is not a neutral process. The ‘meaning’ a governing body chooses to put on a pedestal – and thus, the interpretation of history it decides is “worthy of civic honor” – matters. If the state erects monuments which honor the harming of historically-oppressed groups, that interpretation of history is placed in a position of esteem, and the process of memory-making moves from one of pluralistic historical conversation to become a way of “continuing the war by other means”. Worse still, that interpretation of history quickly becomes the state-sponsored manner of remembering the past, to the detriment of minority groups.

The History of Confederate Monuments in the United States

At present, according to the Southern Poverty Law Center, 1.740 Confederate monuments still stand throughout the United States, honoring figures from the so-called ‘War Between the States’ (as the South calls the Civil War), such as Robert E. Lee, Jefferson Davis, and Thomas Jonathan “Stonewall” Jackson. These take the form of school names (105), monuments and statues (772), street names, public land names, military bases, and more. This figure also includes holidays; eleven states have public holidays codified into their state laws, of which five states celebrate a total of nine holidays on which workers receive paid time off of work. Five states still feature the Confederate flag in prominent positions, either physically on state buildings like Capitols or courthouses, or symbolically on their flags.

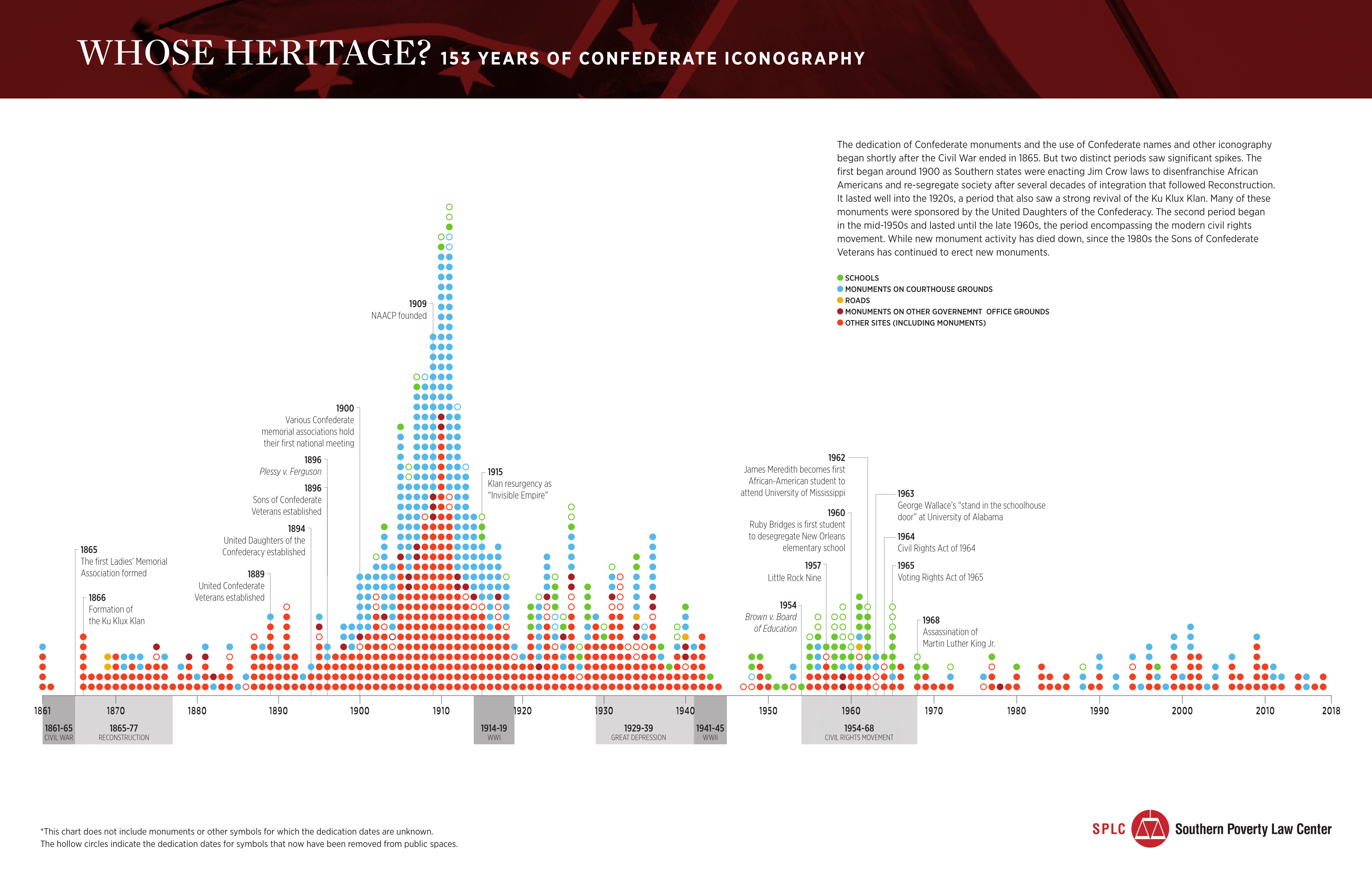

Interestingly, these monuments do not only stand in the former Confederacy, but can also be found in California, Missouri, Kentucky, and New York, among others. This is because the majority of the 1.740 still-standing monuments were not created during Reconstruction, or indeed within three decades of the Civil War’s end. According to a verified tally by the Southern Poverty Law Centre in July 2018, the placement of Confederate monuments generally came in two waves: between 1900 and 1940 and from the mid-1950s to the late 1960s. Those periods also align with two important eras in American history – the establishment of the ‘Jim Crow’ system of racial segregation laws and the Civil Rights Movement. According to the well-endorsed American Historical Association’s 2017 “Statement on Confederate Monuments”, these monuments “commemorate[ed] not just the Confederacy but also the ‘Redemption’ of the South after Reconstruction”, and “were intended, in part, to obscure the terrorism required to overthrow Reconstruction, and to intimidate African Americans politically and isolate them from political life.”

This chart by the Southern Poverty Law Center shows the year of creation of all verified Confederate monuments in the United States.

People of Color, in particular Black communities, have long called for these monuments to be removed, but, according to the Southern Poverty Law Center report, this issue has especially come under international scrutiny since 2015. On June 17, 2015 – five days prior to the 150th anniversary of the end of the Civil War – Dylann Roof attacked a church in Charleston, South Carolina, killing nine people. Later investigation revealed photographs of the shooter in front of a Confederate flag. In the aftermath, calls to remove Confederate monuments in public spaces were amplified, and a national movement began.

A countermovement also surfaced, spearheaded by groups including the Sons of Confederate Veterans, who, in their own words, seek to fight against “the hatred being levelled against our glorious ancestors by radical leftists who seek to erase our history”. As this debate has increased in volume, three new state laws have passed preventing (Confederate) monument removal. The other three existent state laws have changed in their applications, and even undergone amendments, to ensure protection for Confederate monuments. It is in the context of this virulent debate that the six laws preventing monument removal must be examined.

Applicable Memory Laws

Six former Confederate states have laws protecting monuments on public land, three of which have been passed in the last five years. Many of these laws contain four similar elements.

- The prohibition on removing monuments, loosely defined. (Often temporary removals are possible, on strict deadlines to return the monument to its previous location.)

- The establishment or broadening of the mandate of state “Historical Commissions”, responsible for adjudicating petitions for monument removal;

- The establishment of procedural obstacles preventing public entities from successfully petitioning for a monument’s removal;

- The establishment of a punishment for violating the above elements.

The focus of these laws is on the ability of public entities to remove, relocate, rename, or otherwise alter monuments, including Confederate monuments, on public land or ownership. Private entities that attempt to remove public monuments without formal approval are committing vandalism, and are not the concern of these provisions.

‘Monument’ as used in this post is a term of art that may encompass anything from statues to street signs to park names. The term does not include privately owned objects on private land. Historical objects owned by government transportation bodies or port authorities are also typically excluded, though some laws have provisions obliging public entities to preserve them as much as is possible. ‘Removal’ will also be loosely defined to encompass a public act to remove, permanently relocate, alter, rededicate, or otherwise change a monument.

The next section will analyze the six state laws that prevent the removal of monuments, with a focus on the steps required to do so. Each of them creates complex procedures necessary for public entities to remove monuments in their remits. While some of these processes are more laborious than others, none are neutral in their design. Each of the laws are procedurally designed to minimize the success of petitions for a monument’s removal. Moreover, they create biased adjudicators over these petitions; each of the six laws either empowers or creates “Historical Committees” explicitly tasked to preserve historical monuments. While these laws generally apply to any monument (some specify monuments of a certain age, or exclude certain types of monument), they come in the context of the above discourse on Confederate legacies, and cannot be seen as neutral.

Tennessee

Tennessee’s 2013 ‘Heritage Protection’ Bill (Tenn. Code Ann. §4-1-412, as amended in 2016 and 2018) forbids public entities from removing any monument on public property or under public ownership (§b(1)). For a public entity to be exempted from this prohibition, the following is required: a petition, two newspaper articles announcing the initiative in two Tennessee counties, (if applicable) a website posting announcing the initiative, two hearings on the matter, comments from any interested party, a minimum of 180 days before a final hearing can be scheduled, and a written waiver, supported by one or more reports from the claimants proving a “material or substantial need” for the waiver “based on historical or other compelling public interest”. If these requirements are fulfilled, the matter is referred to the Tennessee Historical Commission, which must approve the petition by a 2/3 majority vote (§§c(1-8)).

The Commission is also responsible for adjudicating complaints against public entities allegedly violating the bill. Standing to file complaints is broad (§d), and any entity or individual can file one (§f(2)). If a majority of the Commission finds a violation – that is, if a public entity illegally alters or removes a monument – that public entity is banned from receiving grant contracts from two major government offices (§f(5)). Beside this formal penalty, there have been punitive political measures taken against public entities for removing monuments – even after complying with the above procedure.

North Carolina

North Carolina passed its “Cultural History Artifact Management and Patriotism Act” in February 2015. This bill similarly bans the removal of any monument “that is part of North Carolina’s history” (§3(c)). Exceptions must be approved by the North Carolina Historical Commission, which meets two to four times per year. No punishment is listed for violators of the statute. As of August 2018, the Commission has continuously denied petitions to remove Confederate monuments based on the law, barring one.

Alabama

Alabama’s 2017 Memorial Preservation Act is the furthest-reaching of these laws thus far for three reasons. First, it involves the judicial system in the removal procedure of certain monuments. Second, it requires petitioners to show new facts about the monument or represented figure not known at the time of its creation – otherwise, there is a codified presumption against removal. Third, it allows the Attorney General to issue five-figure fines to public entities in violation of the law.

The law distinguishes monuments less than 20 years old from those 20 years or older. The latter cannot be removed without a court order. The former, younger monuments require a public entity to submit a waiver to the Committee on Alabama Monument Protection. This process requires a resolution from the public entity, “[w]ritten documentation of the origin of the monument, the intent of the sponsoring entity at the time of dedication, and any subsequent alteration, renaming, or other disturbance of the monument”, an opportunity for commentary from any relevant historical institution or the public, and a written statement of new facts about the monument that were not known at the time of its creation (§6(1)(a-d)), and which show the need for its removal. The last requirement is especially arduous: even if one can prove that a hypothetical Confederate figure was a vicious slave-owner, they must also prove that this was not known at the time of the monument’s creation. This allows the Committee to sidestep changes in public values by requiring a change in facts. If this cannot be proven, the petition faces a presumption against removal. Finally, if the Attorney General of Alabama finds that this provision has been violated, he can fine the party responsible $25.000 (§6(f)). This occurred in July 2017 when, months after the Act had been passed, the Attorney General sued the mayor of Birmingham (a majority-Black city) for ‘illegally’ covering a Confederate monument.

A second bill, 2018 SB11, is currently before the Alabama Senate Committee on Education and Youth Affairs. It proposes an amendment to the above Memorial Preservation Act to prohibit the alteration of monuments older than 40 years without exception. Petitions to remove 20 to 40 year-old monuments must undergo the above waiver procedure instead of filing for a court order. As of November 2018, this bill has not moved to either the House or the Senate.

Other States

Since Charleston, three other states have increasingly applied existing statutes to protect Confederate monuments. Mississippi Code § 55-15-81 (2017), originally passed in 1972, forbids the removal of any war-related monuments, though no penalty is explicated.

The 2000 South Carolina Heritage Act notably requires a 2/3 majority vote in the state General Assembly to allow a public entity to remove a monument. After the Charleston massacre, then-Governor (and now US Ambassador to the Security Council) Nikki Haley passed a law to remove a Confederate flag from the State Capitol. Despite legal filings after the fact, this law has remained in place, removing the flag from the state capitol – though other monuments are still protected by the 2000 Heritage Act.

Finally, the 2001 Georgia Code §50-3-1 bans any public entity from altering or removing monuments outright, and the Confederate flag must “be preserved for all time in the capitol as priceless mementos of the cause they represented and of the heroism and patriotism of the men who bore them” (GA C §50-3-5). Private entities violating this provision are committing a misdemeanor crime.

Though some of the above six laws create higher hurdles to a monument’s removal than others do, all of them are cause for concern. The Historical Commissions empowered to adjudicate petitions for removal are opaque in their decision-making processes, biased in their mandates, and prevent more democratic decision-making processes in an issue vital to the interests of minority groups. Particularly problematic are the procedural barriers to a monument’s removal, such as requirements for 2/3 majorities to pass petitions; the establishment of presumptions against removal if certain criteria are not met; the creation of broad standing to complain against violators; the lack of appeals processes in some jurisdictions; and the requirement to unearth new facts about the figure, as opposed to considering changes in public values. Finally, most alarming are the penalties imposed upon public entities perceived to violate the above laws, some of which are decided by politically-appointed figures as opposed to judges, and all of which financially punish public entities for heeding their local community’s calls to remove monuments they consider harmful.

Assessing Monument Removals

Since 2015, Confederate monuments have been increasingly subject to public debate. According to the Southern Poverty Law Center data, 126 Confederate monuments have been removed by public entities from public ground as of July 2018. Curiously, all six states with anti-monument removal laws have removed Confederate monuments. Since their respective laws have passed:

- Tennessee has removed four statues, three park names, and one building name);

- North Carolina has removed five (four statues and one building name);

- Alabama has removed one flag*;

- Mississippi has renamed two schools;

- South Carolina has removed one flag (the one Governor Haley initiated); and

- Georgia has removed six (three monuments, two holidays*, and one street name).

* Those figures asterisked are items that are not protected by the relevant state monument law.

Following the implementation of anti-removal laws, eight cities in these states removed a total of seventeen Confederate monuments protected by those laws. Eleven out of those seventeen monuments were removed in cities where Black citizens are a majority. This suggests that, despite the procedural obstacles created by these laws, public pressure can in some instances still lead to a Confederate monument’s removal.

Though the nationwide conversation has increased every year, particularly since Charleston, its impact is limited. According to the Southern Poverty Law Center figures from July 2018, 7.24% of Confederate monuments in the United States have been removed. At the same time, procedural barriers to adjudicating a monument’s removal have arisen in six states, some of which carry punishments for violating procedure. Furthermore, laws similar to (and, at times, directly adopting language from) these laws have been proposed by other state legislatures.

Conclusion

Current data suggests that the obstacles created by these laws to prevent monument removal can be surmounted, at least in some instances. In spite of the arduous processes described in the laws above, a handful of monuments have indeed been taken down. While the precise extent of the influence of these laws remains unclear, they no doubt present obstacles to the success of petitions for a monument’s removal.

This post repeatedly cited the Southern Poverty Law Center’s report, which includes data of every Confederate monument verified as of July 2018. Reports like these are crucial to understanding the breadth of this issue, as well as the effect laws like the above have in practice. The first step to assessing how a polity deals with its crimes of the past simply must be an analysis of the status quo. Before anything else, someone has to count and document the monuments. In this case, doing so reveals an ongoing and unsolved issue. Though calls to do so have increased every year, only 7.24% of Confederate monuments have been removed. The removals we do see are the exceptions, not the rule.

On the subject of rules, six states have passed laws reinforcing their officially-sanctioned version of the Civil War. Though the Charleston Massacre in 2015 may have amplified the movement to take down Confederate monuments, laws preventing their removal have since doubled in number. Though they are phrased in language that suggests a democratic process, these laws in fact hand the decision to opaque state committees tasked to preserve (Confederate) monuments as much as possible, disadvantaging petitioners. Even a cursory glance at the titles of the laws in question and the committees they create makes it clear that these are not neutral adjudicators. The processes they establish are unreasonably laborious for those petitioning for a monument’s removal. Worse still, none of the above laws explicate remedies for public entities whose petition to remove a monument is denied. Many of the laws give broad standing to file complaints against public entities perceived to be in violation of them. Most troubling are the punishments for public entities found to be in violation.

History decided by committee, especially one predisposed towards an interpretation harmful to minority groups, is not aligned with the democratic decision-making processes that are expected in inclusive, plural societies. If the United States, and especially the American South, is to deal with the lingering legacy of past atrocities, it should amplify the voices it has historically silenced, not exclude them further. As long as ‘our history’ is legally confined to represent a select group, to the exclusion of others, it isn’t ‘ours’ at all – and neither is it history.

Cris van Eijk is an American-Dutch intern for the Netherlands Team of the MELA Project, working from the Asser Institute in The Hague. He holds a BA cum laude in International Justice from Leiden University College The Hague, and is in the final stages of his LLM in Public International Law at Leiden University.